Seaweed by the tonne and singing to seals – life on North Uist

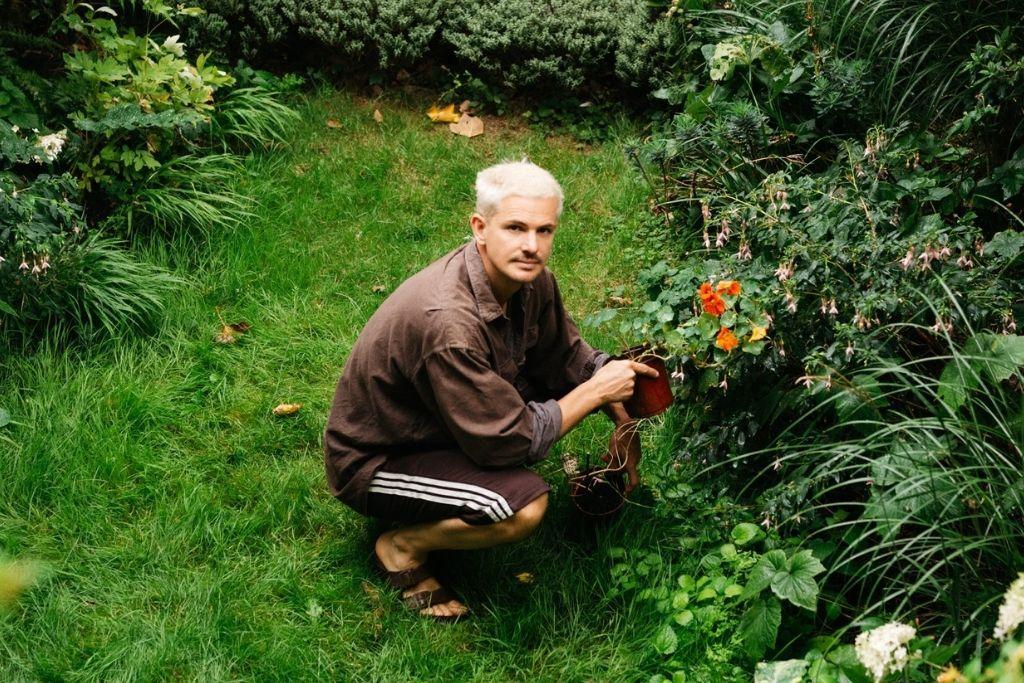

Alexander Thompson-Byer talks about life in the remote Outer Hebrides, harvesting seaweed by hand and how he knows seals don’t like Barry White

Alexander Thompson-Byer has come to a special spot to talk to me. Special in a couple of ways. First, he likes the view over the sea, as it washes in and out of a deep bay on the island of North Uist. Second, it’s one of the few places he reckons he can get a phone signal consistent enough for a long conversation. As Alex is about to tell me, life on the western isles is full of quirks like that.

North Uist is part of a ragged strip of islands that forms the outer edge of the Outer Hebrides. Start sailing west and, unless you bump into the lonely rocks of St Kilda, the next solid ground you’ll see is Newfoundland. Even from Edinburgh, it’s eight hours’ drive and a ferry that leaves from the tip of Skye. It’s easy to understand why I’m not talking to Alex face to face. What’s not so easy to understand is why a London-born landscaper is here harvesting seaweed. And yet, here he is.

Alex moved to North Uist in 2020, as he and his then partner, who grew up on the island, left London. Alex was managing his own gardening business, crossing the city back and forth several times a day. It was gruelling and frantic. “Commuting from Crawley to work, emptying rubbish from the jobs, a two-hour journey each way. It was just too much. The house, the job, the city, everything was stressful and I thought there must be a way to live a chilled life.”

There was also no room to grow, literally. For someone keen on the principles of permaculture and rewilding, an urban garden was limiting. Alex recalls using cuttings from client projects to build a giant compost heap near his house, watching as the ground around it burst into bloom and became a mini wildlife haven. He was always going to need a bit more freedom than the city allowed.

But it was more than the space and speed of London that made Alex hunger for change. There was a deeper issue. “I got stopped by police when I was 16 and that set something in me for life. I used to run everywhere, and I’d saved all my money for a camera bag and was going to show it to a friend. They just saw a black kid running, with something expensive.” Although perhaps the most impactful incident, that was far from an isolated one. “Those sorts of micro aggressions, that sort of thing was always there. I used to try my best to appease people, not to be a ‘scary black man’, but sometimes I’d be walking around with a pickaxe or a spade and I felt I had to be try and say, “I’m not coming to chop your head off, I’m just digging a pond.” I shouldn’t have to do that.”

So Uist had a lot to deliver on – open land, a calmer life, a more welcoming community – but as I begin to ask Alex if it managed to live up to his hopes, I see his focus shift from the camera to something in the distance. He leans forward, stares for a second, then says, “Seals! There are seals down in the bay”. He flips the phone over and I can see, or convince myself I’m seeing, grey shapes splashing in the water far below. While the wildlife spotting is at best ambiguous, the breathtaking view is clear, as ribbons of green land and blue sea weave a pattern all the way to the horizon. It’s as different from an urban environment as you can get. I ask again whether it’s as idyllic as it appears.

“Life is easier, less complicated.” Alex begins, “I’m sitting on a hill I just drove up and there’s no speedbumps, no traffic lights, no traffic wardens. My front door at home is open, the shed is open, I’ve got an outboard, a good one, just sitting on a pallet in plain view. It’s so different I don’t think you can compare it. The sky is 80% of my world and there’s so much land.”

He describes his croft, with more room than he could ever have dreamed of in London, staffed by what he calls his “workmates” – an array of chickens, sheep and other animals who all have a role to play in land management. Thanks to his careful stewardship, the soil is fertile and the garden producing medicinal herbs, root vegetables and everything in between.

Suddenly aware that he’s making it all sound a bit too easy, Alex points out that his Instagram handle is @growing.in.the.wind. “I’ll be driving up to the croft and see a piece of wood by the side of road that I recognise. It’s been blown down from the farm. You have to grow things that are tough and become tough yourself, especially in winter. At times, I’m risking my life just to plant trees. It can be a bit overwhelming but it’s just lush when you’re somewhere like here, looking at the water.”

Which puts big ticks in the boxes for space and calm, but what about the community spirit? Alex lights up and launches into a description of a motley group of crofters, sculptors, writers and all sorts, spread along the loop of the island’s single road, functioning together in a way which is hard for the 9-to-5 urbanite to fathom. “On paper Uist can seem very poor, but maybe if I do something for someone, they’ll give me some fish. Or I’ll help out with someone’s sheep and then they’ll give me a hand with mine.”

I say it sounds like paradise, but Alex shakes his head and thinks for a second. “It’s beautiful and there’s no stresses, but it’s just you. Some people expand into that space but it can make some a bit crazy.” Several aspiring crofters have come out to visit and try their hand at island life. So far none have stayed. “One guy came to work with me and he had this anger in him and I just knew it wasn’t going to work. It’s not the place for that. You have to come with a certain mindset, or it’ll break you.”

"When I moved here, I had my issues and stuff, like we all do, but here when you sit and think, it’s still. In London, you're sitting there dwelling on the stress and then a train goes blasting past or a siren goes off. Or you can go out and be with your friends and forget it all. Whereas here there’s not much to do – just contemplate on another level. You go for a walk and hear your breathing, your heartbeat. And you have to just be ok, with yourself, in this special place.”

And you obviously have to start harvesting seaweed, I suggest, having grown curious about its absence from the conversation until now. Alex grins and nods, “Now that’s something you have to be tough for.” It turns out that seaweed is one of Uist’s very few exports. A small group of independent harvesters, of which Alex is one, spend parts of their spring and summer seeking out patches of wrack and wading into the freezing sea to cut the long fronds by hand then drag them back to shore in nets. The crop is sold by the tonne to companies who process it for use in various products.

“Two hours before low tide, you set the nets. Then you start cutting when the tide moves, balling it up as you go.” It sounds like lonely work, but sometimes the locals come by to say hello. “I’ll be cutting away and then hear this ‘shhhhh’. I’ll turn round and see a seal, just popping up to check me out. I’ve tried singing to them and they didn’t think much of my Barry White, but if I make some of the noises they make, they sometimes stick around.”

Even though it’s a seasonal trade, it’s not as if the water is warm even at the peak of summer, but the intense work of the cutting keeps Alex’s mind off the temperature. “The coldest bit is sitting on the boat on the way back, having been waist deep in the water. Sometimes you feel like you’re not moving, when you’re towing and the tide’s against you. Sometimes the seaweed gets loose and you watch it for ten, fifteen minutes, moving so slowly it’s still in view.”

For Alex, it’s a perfect embodiment of life on Uist – calm, hard, cold and beautiful all at once, with a seasonality that makes it a fitting part of his relationship to the land. As he outlines a plan for a longer “seaweed scythe” to ease the strain of the work, the call quality starts to waver, as if the signal itself is tired of travelling all that way from somewhere so remote. So, I quickly ask him if he misses anything from his urban past. He shrugs.

“I still go to London sometimes, but it’s different now that I know I’ll be coming back here. When I get off the ferry, I take a deep breath and I always think... yes, this is lush.” He lets out a long sigh and I thank him for his time, hoping he heard me. I hang up with the feeling that the mystery isn’t so much how a London-based landscaper ended up here, it’s why more of us, toughness and mindset permitting of course, don’t go in search of somewhere similar and something different from the life we know.

Words by Christopher-Wilson Elmes

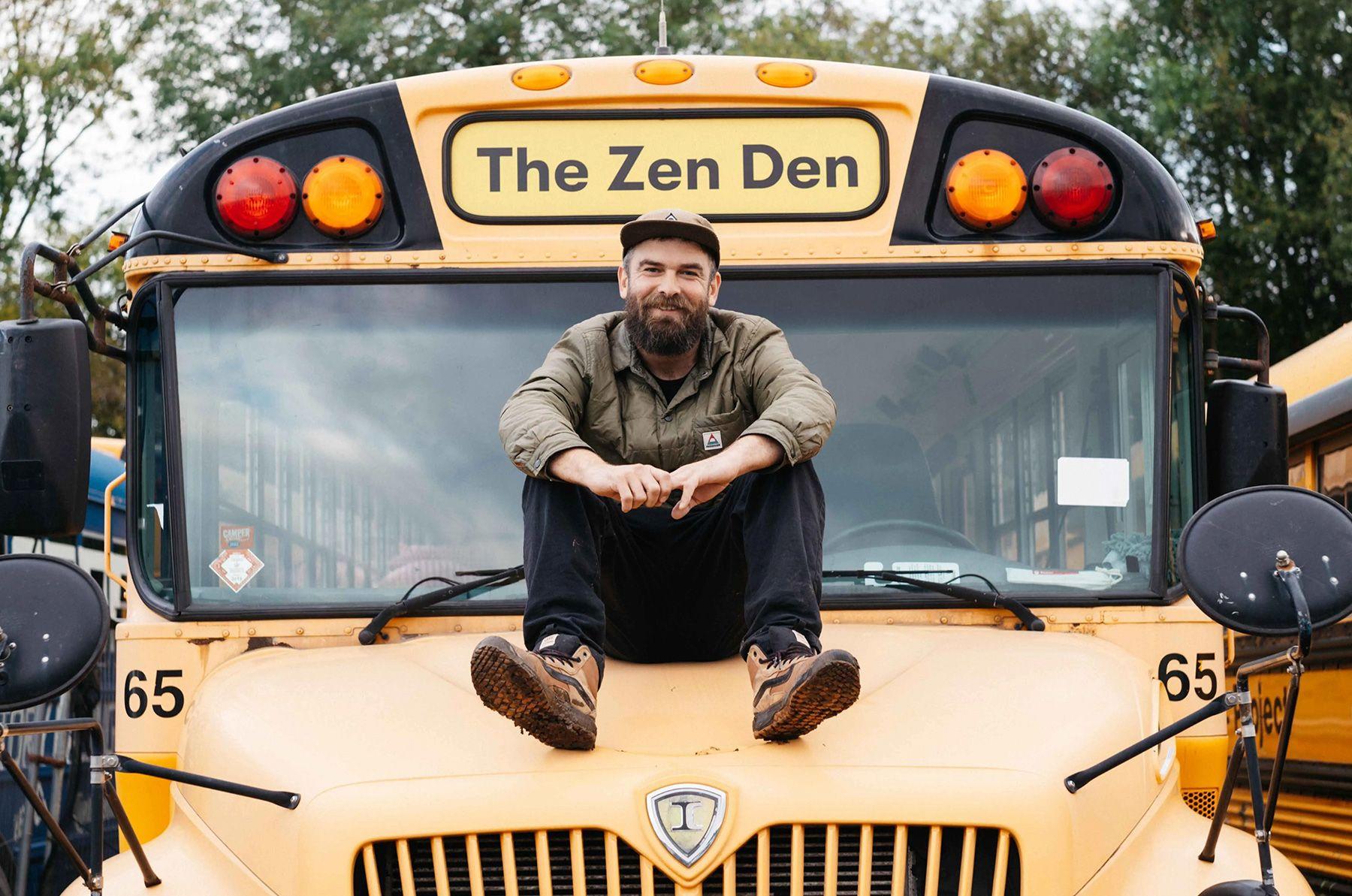

Featuring Alexander Thompson-Byer