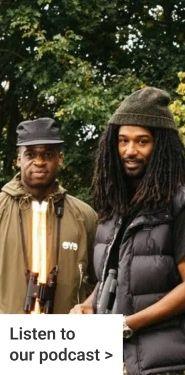

From hobby to revolution: the birdwatcher who’s redefining outdoor culture

Ollie Olanipekun, co-founder of Flock Together turned a love of birding into a global movement.

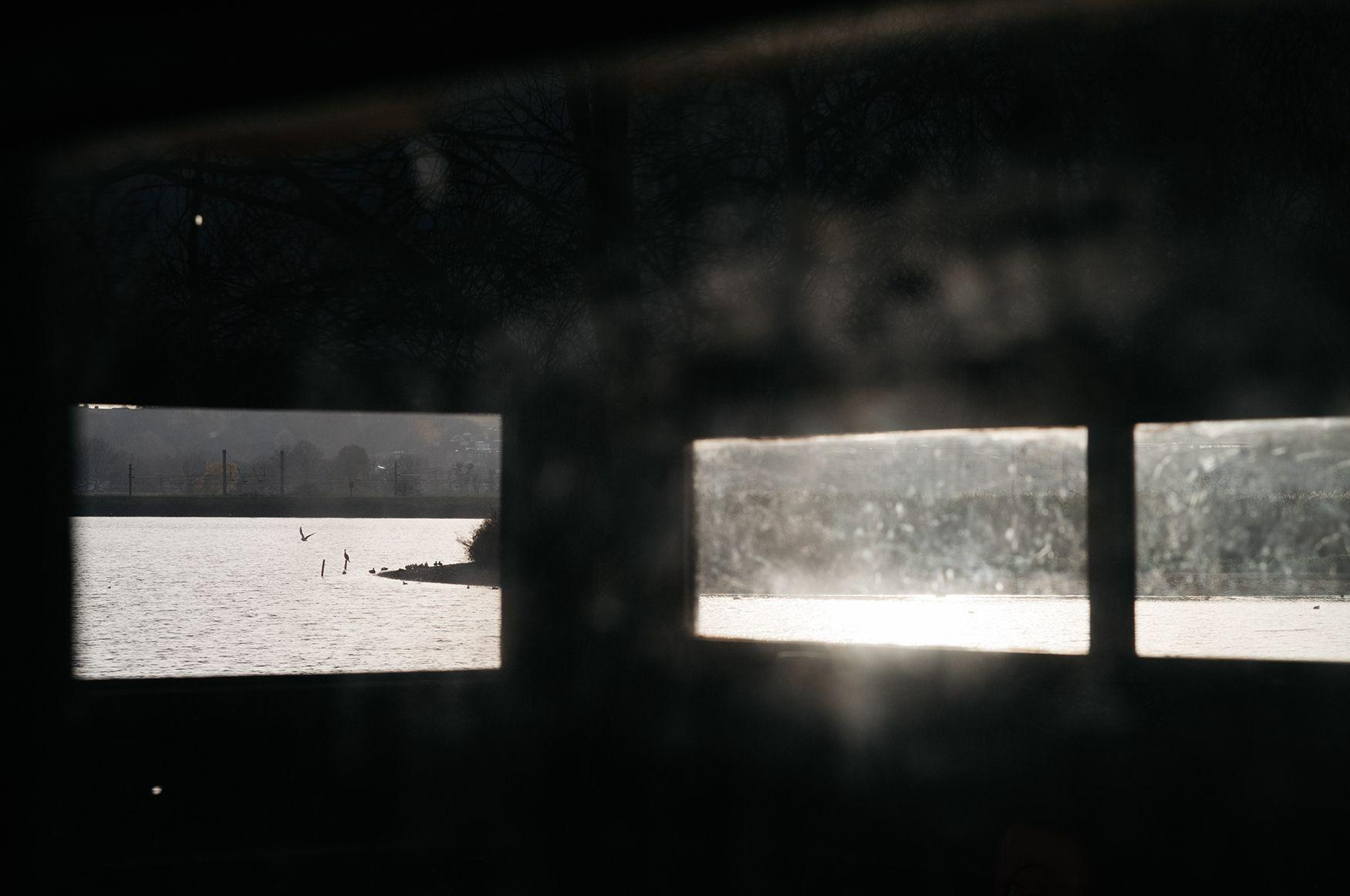

Ollie Olanipekun is a bird watcher. It’s obvious from the moment we start talking. He’s walking back from a meeting, there’s birdsong coming from nearby trees and I can tell it takes him a certain amount of concentration not to scan for them. Birding is more than a pastime, it’s something he loves, a calm space that helps with his ADHD and gives him a way to truly relax. During Covid, he saw a community, people of colour, desperately in need of the connection to nature he’d always had. So, he and his friend Nadeem Perera organised a birding and walking group. Like many groups formed around that time, it flourished as people discovered what getting outside could give them. Unlike most of them, it didn’t fade once the catalyst of Covid had gone. It had Ollie to drive it.

From that first walk in Walthamstow wetlands, Ollie, a creative director by trade, saw immediately what he had on his hands. The birding was secondary, the walks were a space where people of colour could find not only peace in nature but support from each other as well. “In the black community,” he explains, “we don't talk about mental health, it's very much just get on with it.” He knew that Flock Together could change that, and possibly much more, but the approach was everything. Aggression and activism had failed, it was time for something with a bit more flair.

"That aggressive approach hasn't worked. We try and keep it positive."

Where many campaigners and activists focus on pushing existing institutions towards change, Ollie and Nadeem were set on doing things differently. “That aggressive approach hasn’t worked.” he says, not with bitterness but as a simple statement. “We’ve all tried it, but these big organisations are like those massive tanker ships, they take a lot to turn. Most of them don’t really want to change anyway. We try and keep it positive.” Ollie and Nadeem quickly concluded that instead of breaking into the traditionally white world of birding or outdoor pursuits, they would create their own, not exclusively for people of colour, but led by them. The accessibility of birding was the hook, but it was more about the culture that surrounded it.

The perceptions they were fighting against are so ingrained in the world of outdoor experiences that it can be easy to underestimate them. “it’s all... you have to have this knowledge, you have to have this gear, or nature just isn’t for you.” says Ollie. “At Flock, we never dictate the experience in any way, it’s one of the reasons we’ve been so successful.” He talks about travelling with white people in Japan, where Flock Together has a hugely popular chapter. He saw them feel, often for the first time, the sense of otherness with which people of colour are all too familiar. “It’s that feeling, sure, but there are so many factors.” he points out, “You see it in media, marketing, the people we put on pedestals in that space. It’s a subtle but powerful negative message for POC.”

Changing that established picture has been one of Flock Together’s great successes. Ollie and Nadeem have worked with North Face and Gucci, and appeared in Vogue, helping a broader audience see themselves in that world and giving birding and the simple joy of the outdoors a new look. They set out, as Ollie himself says with a mock-sheepish smile, "to make birding sexy." It worked, but a popular platform and partnership work has its perils, so I edge nervously towards a discussion about companies being exploitative of the movement and its founders.

"We see the looks on their faces, feel the force of it and think, “we can never not do this.”

“Oh tokenism is real, for sure. You have to kiss a lot of frogs,” he laughs. I start to feel distinctly amphibious, but he politely steers away from that discussion, “we’re self-funded, so that work is how we keep going. It’s endless, but the good ones outweigh the bads. We collaborate with institutions, brands, organisations, to open up and ensure there's that, you know, mix of cultures, and that's the future. I just think allowing organizations like flock together to curate and design those experiences is really important. We’re not here to point fingers, let's just find ways that we can all improve.”

I suggest that this sounds like a full-time job on top of his actual full-time job and Ollie smiles, “When we first started Flock, my girlfriend asked me if I was sure I really wanted to do it. She knows how I get when I’m into something. But Flock is always in a state of constant evolution. We don't say, this is it today, and it'll be like this forever. It's okay, cool, but how about this? That didn't really work. Okay, cool But what did we learn from that?”

While Flock Together’s approach is in constant evolution, some parts have changed very little in the five years since its founding. The format of the walks and the organisation is still the same, with no attempt made to force anything, no prerequisites, no booking system, no membership scheme and no wider team, just Ollie and Nadeem. I ask if there are any plans to expand and Ollie hesitates before voicing a thought that feels like it’s been in his mind for a while, “If Flock Together is going to be what it could be, maybe it needs more. I’d love to make it a CIC, give it a structure that would help it really grow.”

I ask if that would mean him stepping away completely and he laughs again. He says he’s tired, but the liveliness in his voice and the speed with which his thoughts pour out suggests that his version of tired might be several levels of energy above the rest of us. “There are mornings,” he says, “when we’ve got walks scheduled, and me and Nadeem are like, “I almost can’t be bothered.” But then we go out there and hear the conversations people are having, see the looks on their faces, feel the force of it and think, “we can never not do this.”

That commitment has taken Flock Together to incredible heights. It has reached thousands of people directly and countless numbers with the power of its message. Talking to Ollie, it’s clear that showing people what nature can give them and helping them find their place in it has been hugely rewarding for him, but I ask if it’s come at the cost of his own sanctuary.

Has turning birding into a beacon and the outdoors into a kind of workplace changed his own relationship with them both? He answers immediately, “I don’t think that’s ever possible. Around year three or four, maybe, I lost touch a little, but I’m in love with birdwatching so much. Most of my weekends are spent travelling out into nature, on my own. That’s my safe space. It’s what I need. It’s natural for me. Even now, from where I’m standing, I can see bird feeders and I’m going over to them.”

With a few final pleasantries, we end our conversation and he does exactly that. The man who runs a global movement transforming the outdoors is gone. Ollie Olanipekun is a birdwatcher again.